The Paris Flea Market: Les Puces de Paris, Saint-Ouen

My introduction to 'The Paris Flea Market' (2024, Prestel) is a deep dive into the market of yesterday and today, and gives you all the hacks for navigating and shopping the market.

Stretching out over almost five acres at the northern gates of Paris, just beyond the boulevard périphérique, or ring road, lies the world’s most epic antiques, collectibles and junk market. A wild and sprawling city within a city, strange and enchanted, the Puces de Paris Saint-Ouen flea market is without equivalent in the world.

My book ‘The Paris Flea Market’ (2024, Prestel) draws back the curtain on the much-talked-about but actually quite secret and impenetrable world of the Puces, presenting a sample of the dealers at its heart. Bright constellations in a crowded galaxy, each one an avatar of a particular expertise, they show us memorable finds and conjure private voodoo. They introduce us to artisans and other essential collaborators, share personal Paris landmarks, let us in on trade secrets. This book gives you a chance to look closely at this cluster of stars as if through a telescope, leaning in and focusing until everything begins to gleam.

The Puces, taken as a whole, requires you to correct your vision; to adjust eyes that have been trained by the twenty-first century, in the tidy shops, malls, catalogues and e-shops of the West, loaded with their perfect industrially made products, uniform and predictable, available in every size and colour. The Puces asks you to upturn typical shopping habits, to favour instinct over advertising, personality over perfection, eccentricity over good taste, mystery over rationality, one-off and hand-made over factory-made, yesterday over tomorrow, mess over order, and poetry over business.

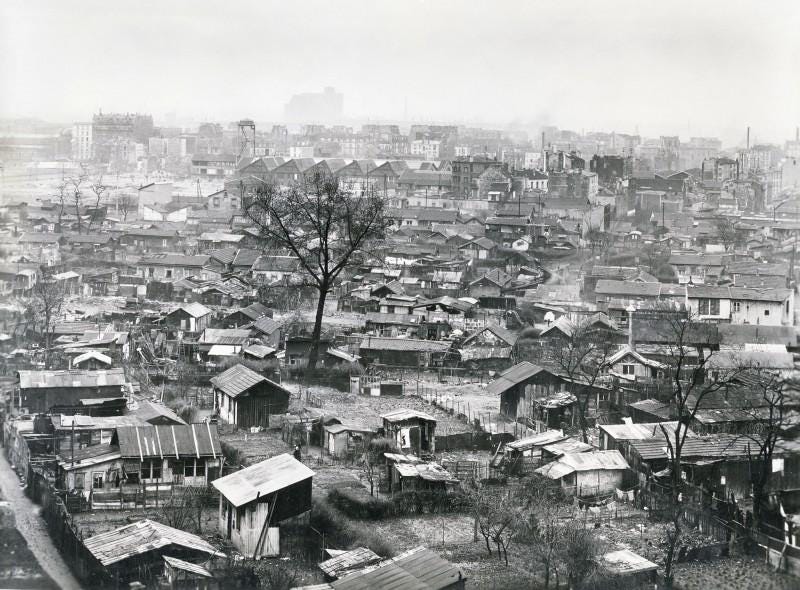

This curious and crazy place evolved out of a unique conjunction of circumstances – geographical, cultural, and political – catalysed by Baron Eugene von Haussmann’s radical modernization of Paris that began in 1853. The disparate bunch of dealers there today, like those at the other Paris flea markets of Montreuil and Vanves, descend from a community of chiffonniers, or ragpickers. Along with many other ‘undesirables’ – migrants, Gypsies, Jews, the poor – they began to settle in a borderland in between Paris and its surrounding suburbs known as la Zone. This 250-metre-wide, non-constructible military belt ran alongside the Thiers wall, Paris’s last set of fortifications completed in 1844, and became a kind of shanty town ringing the capital.

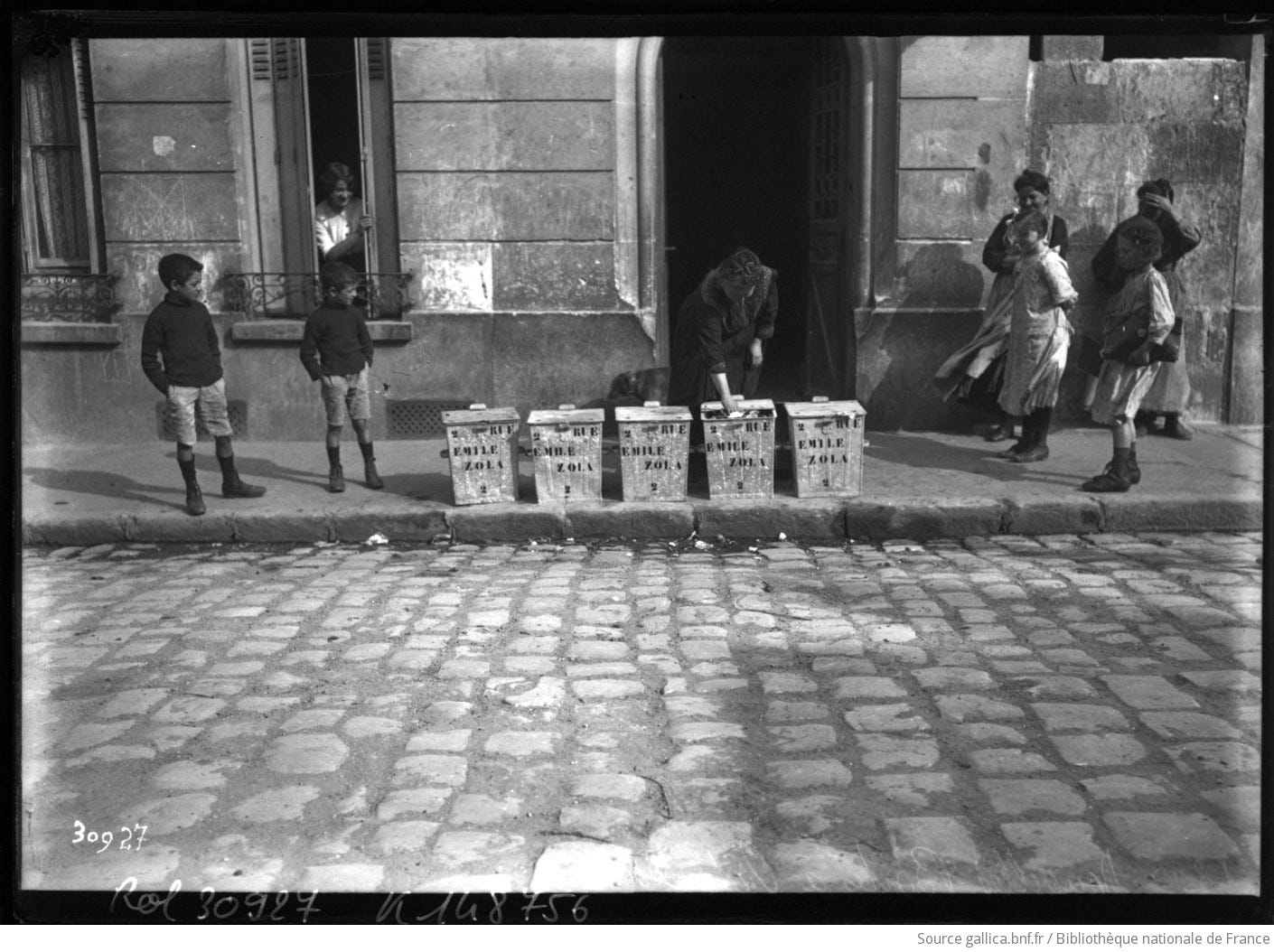

Chiffonniers, or biffins, as they’re known in the local Parisian argot, were firmly entrenched in the daily life of Paris by then. Pliers of an ancient profession, for centuries they played a vital part in the removal and recycling of the city’s waste. Each night, many thousands of them sifted through what was left out for the streetsweepers, recuperating not just the chiffons, or rags, which were reused to make paper, but many other interesting and useful scraps too. La Vargouleme, a chiffonnier in Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel Les Misérables describes how he handled his haul:

‘In the morning, on my return home, I pick over my basket, I sort my things. This makes heaps in my room. I put the rags in a basket, the cores and stalks in a bucket, the linen in my cupboard, the woollen stuff in my commode, the old papers in the corner of the window, the things that are good to eat in my bowl, the bits of glass in my fireplace, the old shoes behind my door, and the bones under my bed.’

Near the bottom of the social order with drunks, beggars and prostitutes, and with a well-earned reputation for proud and savage independence, the chiffonniers both fascinated and repulsed polite society. Artists and writers, from Baudelaire to Manet, were inspired by their outsider vagabond status, and even identified with it. Photographers like Eugène Atget and Germaine Krull brought them out of the shadows, into the light.

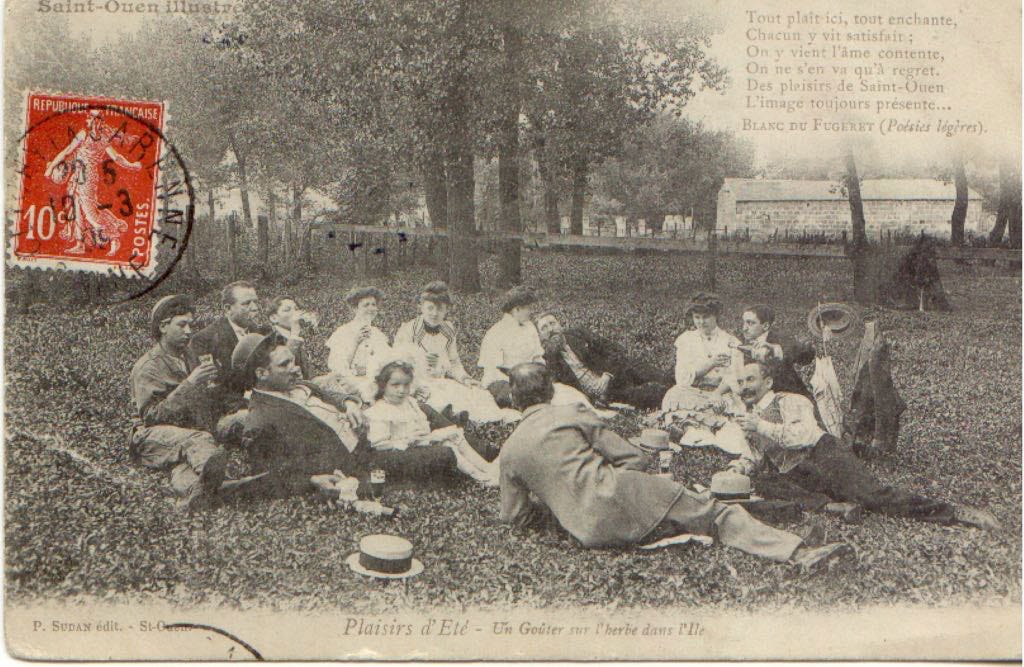

Lying just to the north of la Zone and its community of ragpickers was the village of Saint-Ouen, like so many other riverside villages ringing Paris, a destination much loved by Sunday strollers. On their day off, working-class Parisians might wander up from Montmartre, through the Porte de Clignancourt, stopping perhaps on the grassy ramparts of the fortifs, before continuing on to Saint-Ouen to enjoy its bars and guinguettes serving a cheap local white, or to try their luck at its racecourse, which was built in 1880.

This Sunday exodus – which you can see celebrated in the work of artists including Monet, Caillebotte, Van Gogh, Seurat or Renoir – provided a steady clientele for the chiffonniers. Alongside them there emerged brocanteurs, more specialized second-hand traders with their own sources and methods. Though after 1883, both would have to contend with the new-fangled rubbish bin, imposed by town prefect Eugène Poubelle, which complicated their businesses. (Poubelle is still the word used for rubbish bin in French today.)

As the city organized its disposal rules, the Puces took shape to provide an officially sanctioned selling ground. From 1891, a fee was demanded from those who unpacked their finds along the pavement of the Avenue Michelet on Sunday. Around the same time, the area started to develop and upscale: the Metro came to the Porte de Clignancourt in 1908, the streets of Saint-Ouen were paved, and the fortifications that divided the village from the city centre were demolished in 1919.

After the First World War, the trade in second-hand goods began to specialize, and collectors followed in its wake. Businesses grew to meet demand, and entrepreneurs bought up land to equip it with simple stalls they rented out to merchants. Romain Vernaison, a concessionaire at Les Halles food market, who also rented chairs in Parisian public gardens, installed prefabricated wooden huts on land he owned in Saint-Ouen – some of them are still standing – and the Puces’ first properly structured market opened in 1920. It still bears his name today.

The Puces, with its incongruous profusion and juxtapositions, at the intersection of the primitive and the sophisticated, of dreams and waking reality, was a lodestar for the Surrealists. Artists like Alberto Giacometti and André Breton found a fecund site for the hasard objectif, or objective chance encounter, as well as the objet trouvé, or found object. For them, the synchronicities that were so easily occasioned at the Puces catalysed thoughts and desires, and let the unconscious speak. ‘I go there often, searching for objects that can be found nowhere else: old-fashioned, broken, useless, almost incomprehensible, even perverse,’ Breton wrote in his 1928 novel Nadja. Later, after the war, the writer Jacques Prévert, poet of the people and a friend to the Surrealists, created collages from images he found at the Puces. And his poem ‘Inventaire’, a mad and joyous list of seemingly random impressions, could describe a typical day there. (Skip to the book’s endpapers if you have a copy - or click here - to read a fragment of it, alongside its 1958 English translation by Lawrence Ferlinghetti.)

Shopping the Puces today takes you through eleven different markets that function like a collection of tiny neighbourhoods, each with its own history and identity. Having grown organically, not through planning, the different spaces make for a motley compendium of styles and structures. It’s like a delightful favela with very little architectural harmony, modern comfort or conventional beauty, whose eccentricity only adds to its charm.

Every one of the individual markets has its own niche and speciality. Marché Vernaison, the original, looks like what you’d imagine when you hear the words ‘flea market’: a picturesque tangle of alleyways lined with about 250 rickety little stands selling all sorts of bric-à-brac. Stretching over practically 9,000 square metres, it’s the biggest market in the Puces.

Opposite Vernaison, the two-storey, glass-roofed Marché Dauphine opened in 1991 and presents a mix of pop-culture ephemera – records, posters, postcards, books, comics – vintage fashion and accessories, and quality antiques. The Marché Biron, which dates back to 1925, ups the bling factor with a red carpet along its long central avenue, as if it were Cannes during festival time. Biron was the first to sell restored old objects and today specializes in high-end ‘antiquités classiques’, meaning pre-Modern, pre-twentieth-century pieces.

There’s been a major cultural shift at the Puces over the past couple of decades, as twentieth-century furniture overtakes classique, for so long the lifeblood here. Today, the Marché Paul Bert and the adjacent Marché Serpette – a former car park converted in the 70s – both specializing in twentieth-century goods, are the Puces’ most design-forward and high-profile markets.

The long, covered Marché Jules Vallès opened in 1938 and is reputed for having good deals and a rapid turnover of unrestored pieces, attracting many dealers. The Marché L’Usine next door is also more business-to-business, open in principle to professionals only, on weekdays, when the rest of the market is closed. A handful of other, smaller markets complete the picture, including the Marché Malik with its fake Balenciaga and Jacquemus, Nikes or Ray-Bans.

The Puces has always been home to an important number of Jewish dealers, dating back to a first wave of immigration from Russia in the late 1800s. With a cultural history tied to tailoring and clothing repair, many of these immigrants were tailors, hat makers, or dealers in second-hand clothing who found a natural home here. The Marché Paul Bert, created in 1946 on the site of an old vineyard, offered a percentage of its stands to Jewish dealers, which allowed them to resume trade after the devastation and horror of the Second World War.

If the trade at a few of the established markets at the Puces is today exceptionally noble and refined, a few market streets – notably Rue Jules Vallès, Rue Lecuyer and Rue Paul Bert – are home to a mix of makeshift stands, shops, and pavement sellers continuing the trade of the biffins. Everything imaginable that can be sold or collected is found here. Old valves. Sweat socks. Spent ammunition shells. Shoelaces. Doll’s heads. Why not? Everybody’s trash is somebody’s treasure.

From the most hallowed expert and cashed-up collector to the humblest street seller, everyone finds sustenance and joy at a large array of cafés and restaurants scattered throughout the Puces or close by. There are charming traditional bistros, couscous joints, down and dirty dives, the jazz manouche mecca La Chope des Puces, even two separate MOB boutique hotels, with their garden terraces and excellent pizza. Almost all of it has survived Covid, with the sad exception of Chez Louisette, the historic music hall and guinguette once located inside Vernaison market. (All that remains of it now are video clips of its warbling torch singers and day-drunk crowds that haunt the internet like ghosts of the dearly departed.)

Open on the weekends and partly on Mondays too, the Puces draws crowds of tourists and locals who come to wander the alleys, hang out, and chiner. A concept so specifically French it’s essentially untranslatable, chiner means to meander, more or less aimlessly, while perusing old stuff. You can’t chiner new things. It’s not quite antiquing, bargain hunting or digging. It describes a state of browsing without knowing what you’re looking for, a journey more than a destination. Like that other untranslatable French word flâner, which was invented to describe a new, modern relationship to the urban spectacle, chiner is almost a state of mind, a philosophy of life. It’s the religion of the Puces. It’s the art and raison d’être of the dealers.

You can chiner your way through the entire country, as every city, town and neighbourhood throughout France is proud host to regular brocantes and vide-greniers, or garage sales. This French way of life is visible too in the Puces’ colourful demonstration of the Socialist principle of ‘mixité’, or social diversity. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Saint-Ouen, where the Puces was born and thrived, is emblematic of the ‘red belt’ of northeastern suburbs. Between 1945 and 2014, Saint-Ouen had just three mayors, all Communist. Is this what allowed the market to resist the pressures of big business and the property market? At London’s Portobello Market, rising rents and an absence of regulation have seen a once glorious heap of treasures overrun by chains selling new goods, largely tat for tourists. The number of antique dealers there has more than halved since the 90s.

Aside from politics, it’s that blurry poetic thing called ‘atmosphere’ that protects the Puces from the threat of gentrification today. After one fifth of the overall market was lost to property development, in 2001 the Puces was designated a Zone for the Protection of Architectural, Urban, and Landscape Heritage. This status safeguards from destruction or significant modification, and formally recognizes the Puces as a site of intangible heritage, more than the sum of its parts. An application underway for UNESCO World Heritage status should provide even stronger protection, at an international level.

The Puces’ countless dealers – is it one thousand or two? No one seems able to say with any certainty – each participate in their own way in a sinuous human network that empties the houses and apartments of France and Europe, the crumbling châteaux, old shops and factories, safety deposit boxes. Everything humanity has produced, the ill-gotten gains and splendid inheritances, just keep piling up, and the dealers today, like the chiffonniers of the nineteenth century, sift and sort through the mountains of possessions that have been forgotten, lost, reclaimed, confiscated, overlooked, given up, or sacrificed in our collective march through time. All this drains into the Puces like an estuary into the sea.

Typically, each dealer sells what they love most, sharing their passions fully. Each stand is an altar to someone’s unique taste, expertise and obsessions. Few consult trend reports about next season’s favourite colour or conduct keyword searches. Instead, the Puces is a jumble of idiosyncrasy and self-expression. If some dealers have degrees in art history, auctioneering or business, most of them have more improvised CVs. There’s no real school for what they do. Many of the dealers you will meet in these pages continue a family heritage, others fell into the business from individual passion or a chance encounter. The market’s rich character is the collective expression of these largely unconventional lives.

New trends certainly do emerge out of the Puces, though, and each dealer’s taste, expertise and flair contributes, making the old new again, reinvigorating the market with forgotten talents and styles, and teaching wide-eyed chineurs to see differently. Furniture designed by Jean Prouvé and other Modernist architects was worth peanuts before being rediscovered in the 80s by dealers at the Puces. In creating a market for things that used not to have one, dealers reconfigure the landscape of supply and demand. Sometimes it comes from opportunism, seeing the profit in things that are easy and affordable to source, and sometimes through the force of their conviction, and their trailblazing taste.

Another crucial strand of DNA making up the Puces is its flourishing community of highly skilled artisans, many of them working in the old way, out of workshops hidden amongst the market’s streets and alleys. The Puces valorises and maintains artisanal skills that have, in many other cities in the world, almost disappeared. Cabinetmakers, gilders, art restorers, chandelier repairers, ceramic restorers, marble workers, electricians, upholsterers, glassmakers, metalsmiths, and more, give new life and lustre to objects that have already survived decades or centuries.

This open-air museum is a mecca not just for the flâneur, chineur or collector, but also for creative professionals, some of whom you will meet in this book. Decorators, architects, fashion and costume designers, furniture and set designers, artists and artisans of all sorts come to research, source, and buy, now more than ever preferring to recycle, upcycle and restore treasures from the past, rather than continuing to thoughtlessly over-produce.

Visiting the Puces is to land in the middle of an extraordinary catalogue of mankind’s sensibility and imagination. It’s a time machine passing through the history of civilizations, from Ancient Rome to Art Deco, the Middle Ages to Mid-Century Modern, the Renaissance to Memphis Milano, faster and with more fun than Google. A tribute to human endeavour, ingenuity, and love of beauty, it is a privilege to wander its alleys, to be able to soak it up #IRL, to see and touch the objects, sense their vibrations, and observe and mix with this rare human tapestry. The Puces demands new forms of interaction with the environment. With its variety and profusion, it’s an invitation to sharpen your eye. And learning to ‘see’ is an adventure that gets more and more captivating the further you go. The best part of it is, entry is free.